Do Japanese Kids Still Fight? A Manga Sparks Curiosity

Ever reminisced about those childhood spats with friends that sometimes escalated into a full-blown scuffle over the tiniest issues? If you’ve ever wondered whether kids today still get into fistfights or if times have changed, a recent Japanese comic strip from Rocket News might just catch your interest. This quirky piece has us pondering: do modern Japanese elementary schoolers still engage in physical fights, or has the playground dynamic shifted entirely in today’s era? Let’s dive into this lighthearted yet thought-provoking snapshot of Japanese childhood and see what we can learn—both culturally and linguistically.

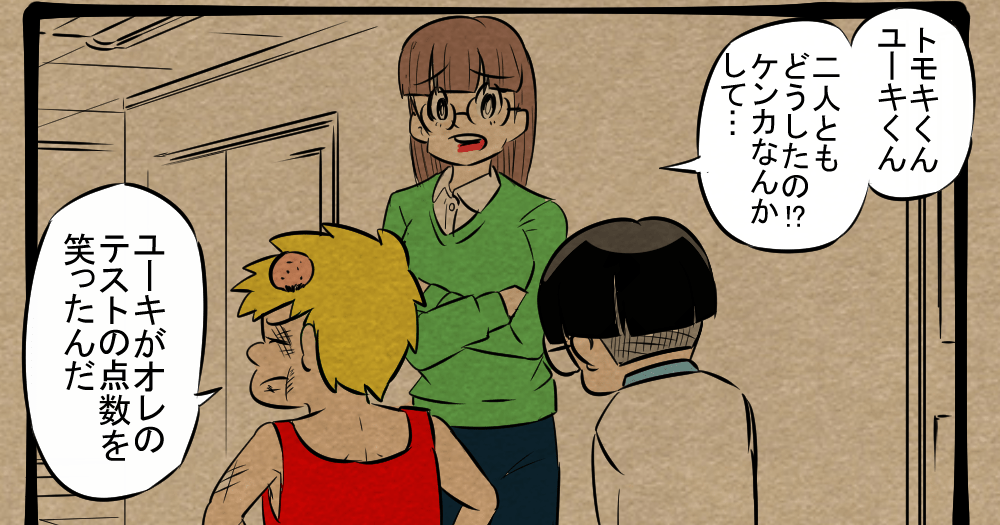

The Comic That Started It All

On December 26, 2025, Rocket News published a four-panel manga titled 完敗 (kanbai), meaning "complete defeat," as part of the Sabotage BYD series by artist Zack KT-4. In just a few frames, the comic humorously depicts a teacher listening to students explain the messy circumstances of a fight. The title hints that someone clearly didn’t come out on top! Alongside the artwork, the accompanying text raises a curious question: do today’s Japanese kids still get into physical altercations like 殴り合い (naguriai, fistfight) with their friends, or is that kind of roughness a relic of the past? It’s a playful yet intriguing look at how generational shifts might be reshaping even the most basic childhood experiences in Japan.

Cultural Lens: Harmony vs. Rough Play

If you’re new to Japanese culture, you might not know that physical fights among kids aren’t often discussed with a nostalgic or humorous tone in Japanese media. Japan’s education system heavily emphasizes the concept of 和 (wa, harmony or peace), prioritizing group cohesion over individual conflict. Rough behavior, described as 荒っぽい (arappoi, rough or wild), can be seen as disrupting this ideal, even among young children. A generation ago, small fights or ケンカ (kenka, fight or argument) might have been dismissed as “kids being kids,” but in modern Japan, with stricter social norms and a focus on safety, such incidents might be less common or taken more seriously by teachers and parents.

This comic also introduces us to a staple of Japanese pop culture: the four-panel manga, or 四コマ (yonkoma). These short strips, often found in newspapers or online, deliver quick humor or social commentary. Their brevity forces artists to pack a punch in just a few images, making them a fantastic way for Japanese learners to glimpse everyday thoughts, values, and casual expressions. It’s a reminder that even a simple fight or 仲違い (nakatagai, falling out or disagreement) can reflect deeper shifts in 時代 (jidai, era or times).

Learn Japanese from This Article

Ready to turn this cultural curiosity into a language lesson? Let’s break down some key vocabulary and grammar inspired by this comic and topic. These words and patterns will help you discuss childhood, conflicts, and societal changes the way native speakers do in Japan.

Key Vocabulary

| Japanese | Romaji | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 仲違い | nakatagai | falling out, disagreement |

| 殴り合い | naguriai | fistfight, physical fight |

| ケンカ | kenka | fight, argument |

| 荒っぽい | arappoi | rough, wild |

| 時代 | jidai | era, times |

| 和 | wa | harmony, peace |

| 小学生 | shougakusei | elementary school student |

These words aren’t just useful for talking about childhood fights—they also open doors to discussing relationships, societal norms, and historical changes. For example, you might hear 小学生 (shougakusei) in everyday conversations about kids, while 和 (wa) is a concept you’ll encounter in discussions of Japanese values.

Grammar Spotlight: 〜たりする (Do Things Like ~)

Let’s look at a versatile grammar pattern that fits perfectly with describing behaviors like those in the comic: 〜たりする. This structure is used to list examples of actions, often implying “doing things like” or “sometimes doing.” It’s casual and great for conversational Japanese.

- Structure: Verb (stem form) + たり + Verb (stem form) + たり + する

- Examples:

- 小学生の時、友達とケンカしたり遊んだりした。 (Shougakusei no toki, tomodachi to kenka shitari asondari shita.) When I was an elementary school student, I fought with friends or played with them.

- 子供たちは走ったり叫んだりすることが多い。 (Kodomo-tachi wa hashittari sakendari suru koto ga ooi.) Kids often do things like running or shouting.

- 昔は兄弟で殴り合いしたり仲違いしたりしたよね。 (Mukashi wa kyoudai de naguriai shitari nakatagai shitari shita yo ne.) Back in the day, siblings used to fight physically or have disagreements, right?

Use 〜たりする when you want to give a sense of variety in actions without listing everything exhaustively. It’s perfect for reminiscing about childhood or describing typical behaviors.

Useful Expression: 〜んだよね (Explanatory Casual Tone)

Another gem to pick up is 〜んだよね, a casual way to explain something with a nuance of “isn’t it?” or “you know?” It adds a conversational, relatable tone to your speech.

- Structure: Sentence (plain form) + んだよね

- Examples:

- 最近の小学生はケンカしないんだよね。 (Saikin no shougakusei wa kenka shinai n da yo ne.) Recent elementary school kids don’t fight, you know?

- 昔は荒っぽい遊びが多かったんだよね。 (Mukashi wa arappoi asobi ga ookatta n da yo ne.) Back then, there were a lot of rough games, isn’t it?

This expression is great for sharing observations or opinions in a friendly, engaging way—perfect for discussing cultural shifts like those hinted at in the comic.

Continue Learning

Want to build on what you’ve learned here? Check out these related lessons from “Japanese from Japan” to deepen your understanding of key concepts:

- Time and Dates: Tense-Free Expressions: Ready to dive deeper? Our lesson on Time and Dates: Tense-Free Expressions will help you master these concepts.

- Wa vs. Ga: Emphasizing Importance in Sentences: To understand more about は, explore our Wa vs. Ga: Emphasizing Importance in Sentences lesson.

- Ni, De, and E: Mapping Directions and Locations: To understand more about に, explore our Ni, De, and E: Mapping Directions and Locations lesson.

Closing Thoughts

Whether or not Japanese kids still get into playground scuffles, this little manga strip reminds us how much culture and language are intertwined with even the smallest aspects of life. By learning words like ケンカ (kenka) and patterns like 〜たりする, you’re not just picking up vocabulary—you’re stepping into the Japanese way of thinking about childhood, harmony, and change. Keep exploring these everyday snippets of Japan with us, and you’ll find your language skills growing alongside your cultural understanding.

これからもよろしくお願いします。 Kore kara mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu.