Rakuten’s Food Loss Lucky Bag: A Deal with a Purpose

Hey there, Japanese learners! If you’ve ever wanted to snag an incredible deal while getting a glimpse into how Japan addresses real-world issues like food waste, you’re in for a treat. Today, we’re diving into a unique offering from Rakuten, Japan’s e-commerce giant, that not only saves you money but also ties into a profound cultural value. Picture this: a box stuffed with snacks and drinks for a steal, all while helping tackle 食品ロス (shokuhin rosu, food loss). Let’s unpack this fascinating story from Rocket News and explore what it reveals about Japanese values and everyday life.

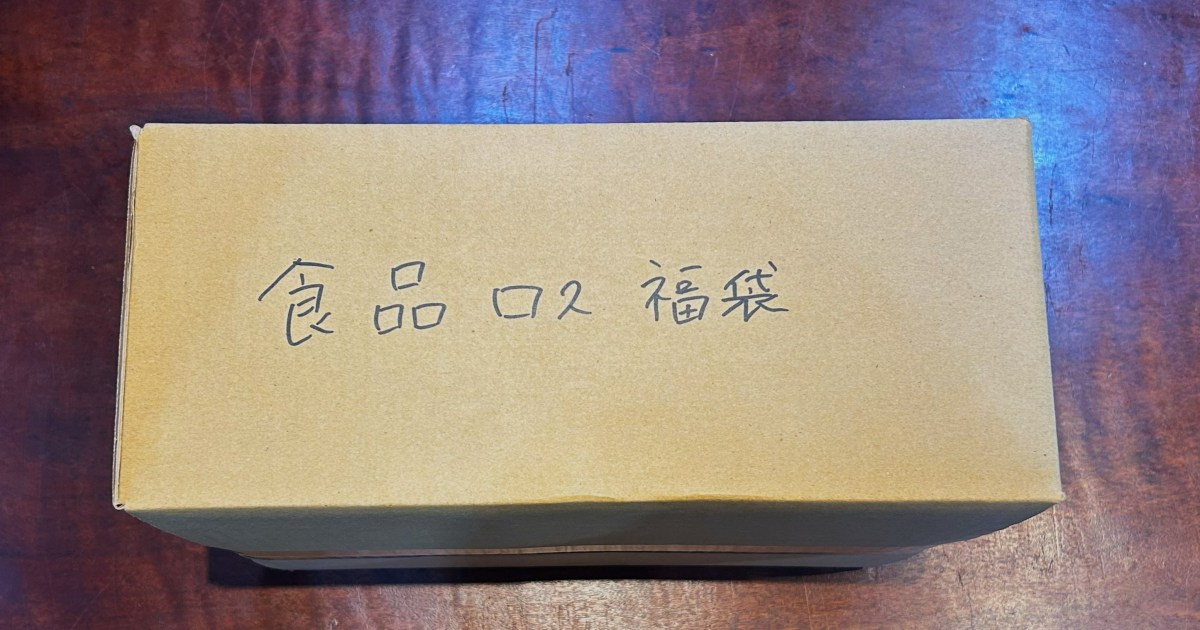

What’s Inside Rakuten’s Food Loss Lucky Bag?

Every year, Rakuten Market rolls out special 福袋 (fukubukuro, lucky bags) designed to reduce food waste. Unlike the typical New Year’s lucky bags filled with random goodies, these are curated to rescue food that might otherwise be discarded. One standout box, under the 監修 (kanshuu, supervision) of the NPO Japan Mottainai Food Center, costs just 1,900 yen (about $13 USD, depending on exchange rates). That’s a bargain for the sheer volume of items packed inside!

The box is a treasure trove of snacks and drinks, featuring items like ばななっ子 (bananako, banana-flavored treats), しるこサンド檸檬 (shiruko sando remon, lemon-flavored sweet bean sandwiches), Fuji Mountain chocolate crunch, and even emergency water with a five-year shelf life. With over 30 individual items—including energy bars and ice syrups—it’s a heavy haul (partly thanks to six bottled drinks!). The catch? Many of these products are past or nearing their 賞味期限 (shoumi kigen, best-before date), though they’re still safe to eat, thanks to the NPO’s oversight.

The author of the original article noted a slight 値上がり (neagari, price increase) from last year’s 1,800 yen to this year’s 1,900 yen for 2025. Still, no one’s complaining about the value. They even sampled items like 林檎のたまご (ringo no tamago, apple-shaped sweets) and found them perfectly tasty, even if past their prime “best by” date.

A Mission Beyond a Bargain

What elevates this beyond a cheap haul is its deeper purpose. Tucked inside the box is a message from the NPO Japan Mottainai Food Center explaining that profits fund efforts to cut down on food waste and support those in need. It’s a nod to the Japanese concept of もったいない (mottainai, wasteful or regrettable), a term that expresses regret over wasting anything—be it food, time, or resources. The author reflects on how much edible food gets tossed just because of expiration dates and commits to buying these boxes yearly to support the cause.

If you’re worried about expired goods, Rakuten’s got you covered. During checkout, you’re repeatedly asked to confirm you’re okay with the contents’ condition, giving you the chance to opt out if it’s not for you. It’s a thoughtful balance of transparency and purpose—perfect for when you’re feeling a bit peckish, or as the Japanese say, 小腹がすく (kohara ga suku, to feel a little hungry).

Cultural Context: The Spirit of Mottainai and Food Loss in Japan

If you’re new to Japanese culture, the idea of もったいない (mottainai) might strike a chord. There’s no direct English equivalent, but it captures a deep aversion to wastefulness, rooted in Japan’s history of scarcity and Buddhist principles of valuing resources. It’s why you’ll see Japanese people meticulously sorting trash for recycling or turning leftovers into new dishes. The issue of 食品ロス (shokuhin rosu, food loss) is a global concern, but Japan’s response often ties back to this cultural ethos. Initiatives like Rakuten’s lucky bags aren’t just practical; they’re a modern take on a centuries-old mindset.

Then there’s the tradition of 福袋 (fukubukuro, lucky bags), typically sold around New Year’s as mystery bags packed with discounted items. While this food loss version isn’t holiday-specific, it borrows the concept to make doing good feel fun and rewarding. Understanding these cultural layers shows how Japanese values shape even something as modern as an online purchase.

Learn Japanese from This Article

Let’s turn this story into a learning opportunity! Here are some key words and grammar points to help you talk about food, waste, and deals like a native speaker.

Key Vocabulary

| Japanese | Romaji | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 食品ロス | shokuhin rosu | food loss, food waste |

| 福袋 | fukubukuro | lucky bag, mystery bag |

| 賞味期限 | shoumi kigen | best-before date, expiration date (for taste) |

| 監修 | kanshuu | supervision, editorial oversight |

| もったいない | mottainai | wasteful, regrettable |

| 値上がり | neagari | price increase |

| 小腹がすく | kohara ga suku | to feel a little hungry |

Grammar Spotlight: 〜ている (Ongoing Action or State)

The pattern 〜ている (~te iru) is used to describe ongoing actions, states, or habitual behaviors. It’s like adding “-ing” in English or indicating something that’s currently happening or regularly done.

- Structure: Verb (て-form) + いる

Examples:

- 私は食品ロスについて考えている。(Watashi wa shokuhin rosu ni tsuite kangaete iru.

- I’m thinking about food loss.)

- 彼はいつも福袋を買っている。(Kare wa itsumo fukubukuro o katte iru.

- He always buys lucky bags.)

- 小腹がすいている時、スナックを食べる。(Kohara ga suite iru toki, sunakku o taberu.

- When I’m feeling a little hungry, I eat a snack.)

- 私は食品ロスについて考えている。(Watashi wa shokuhin rosu ni tsuite kangaete iru.

When to Use: Use 〜ている to describe something happening right now, a current state, or a repeated action. It’s super common in daily conversation, so you’ll hear it everywhere in Japan!

Grammar Spotlight: 〜ても (Even If, Even Though)

The pattern 〜ても (~te mo) means “even if” or “even though,” often used to express a condition that doesn’t change the outcome or to show contrast.

- Structure: Verb/Adjective (て-form) + も

Examples:

- 賞味期限が過ぎても、まだ食べられる。(Shoumi kigen ga sugi te mo, mada taberareru.

- Even if the best-before date has passed, it’s still edible.)

- 値上がりしても、この福袋はお得だ。(Neagari shi te mo, kono fukubukuro wa otoku da.

- Even though the price increased, this lucky bag is still a good deal.)

- 忙しくても、もったいないと思う気持ちを忘れない。(Isogashiku te mo, mottainai to omou kimochi o wasurenai.

- Even if I’m busy, I don’t forget the feeling of regretting waste.)

- 賞味期限が過ぎても、まだ食べられる。(Shoumi kigen ga sugi te mo, mada taberareru.

When to Use: Use 〜ても to soften a statement or show that something happens regardless of a condition. It’s great for polite or nuanced conversations.

Closing Thoughts

Rakuten’s Food Loss Lucky Bag isn’t just about snagging a deal—it’s a window into Japanese culture, from the spirit of もったいない (mottainai) to the joy of 福袋 (fukubukuro). By exploring stories like this, you’re not just learning words; you’re connecting with the values and daily life of Japan. So, next time you’re feeling a little hungry (小腹がすく, kohara ga suku), why not think about how you can reduce waste while enjoying a snack? Keep practicing, and let’s continue this journey together!

これからもよろしくお願いします。 Kore kara mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu.